In early June, the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, and Parkinson’s Movement offered a webinar on research into growth factors in the brain that could potentially be useful for treating neurodegenerative disease. The presentation featured a panel of speakers involved in Parkinson’s disease (PD) research. They discussed the findings of a workshop and consensus paper published in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, describing the types of growth factors that exist, how one can deliver growth factors to the brain, and what clinical trials have been conducted over the years. We at Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach viewed the webinar and are sharing our notes.

The speakers on the panel included:

- Prof. Patrik Brundin: Lead Investigator, Van Andel Institute

- Prof. Howard Federoff: Adjunct professor of Neurology, Georgetown University Medical Center, Aspen Neuroscience

- Prof. Mart Saarma: Director, Saarma Lab, University of Helsinki

- Lyndsey Isaacs: Cure Parkinson’s Trust, Trustee, wife of the late Tom Isaacs, a PD activist

This webinar was recorded and can be viewed here.

If you have questions about the webinar, you can contact The Cure Parkinson’s Trust at helen@cureparkinsons.org.uk.

For a detailed but accessibly-written scientific summary of the research on growth factors and PD up to 2019, see this blog post by Dr. Simon Stott, Deputy Director of Research at The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, available here.

Now… on to our notes from the webinar.

– Lauren

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Neurotrophic factors – Webinar notes

Presented by the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease, The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, and Parkinson’s Movement

June 3, 2020

Summary by Lauren Stroshane, Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach

Growth factors are protein molecules that exist in the body to stimulate cell growth, proliferation, and healing. When found in the brain, they are called neurotrophic factors, which regulate the health and activities of cells in the nervous system. Neurotrophic factors were discovered by Italian scientist Dr. Rita Levi-Montalcini, who would go on to win the Nobel prize in Medicine for her work. Since then, scientists have theorized that certain growth factors might have potential to help those with neurodegenerative illnesses such as Parkinson’s disease (PD).

In this presentation, the panelists discussed:

- Types of growth factors that exist – names, how they differ biologically

- How one can deliver growth factors to the brain – gene therapy, injections, etc

- What clinical trials have been conducted over the years – methods, outcomes

Types of neurotrophic factors

Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is a naturally-occurring growth factor found in the brain that, in lab studies, seems to benefit some of the dopamine-producing neurons in the brain that are affected by PD. GDNF is the subject of both past and ongoing clinical trials into its potential to someday treat PD. Initial results have been very promising, followed by disappointing results in a subsequent placebo-controlled trial.

There may be many possible reasons for this. It is possible that benefits from the treatment that were visible on brain scans did not translate to physical benefits right away. Additionally, the dose administered in the brain might have been too low. PD is a very heterogeneous disease, so perhaps some types of PD would respond better than others. Maybe some of the participants had too extensive disease to revive dopamine neurons that have already died. There are many challenges to this research; determining a sufficient dose of the growth factor and devising an effective delivery method into the brain are both series hurdles.

Neurturin is another neurotrophic growth factor that has also been studied as a possible treatment for PD. It is in the same family as GDNF and functions similarly.

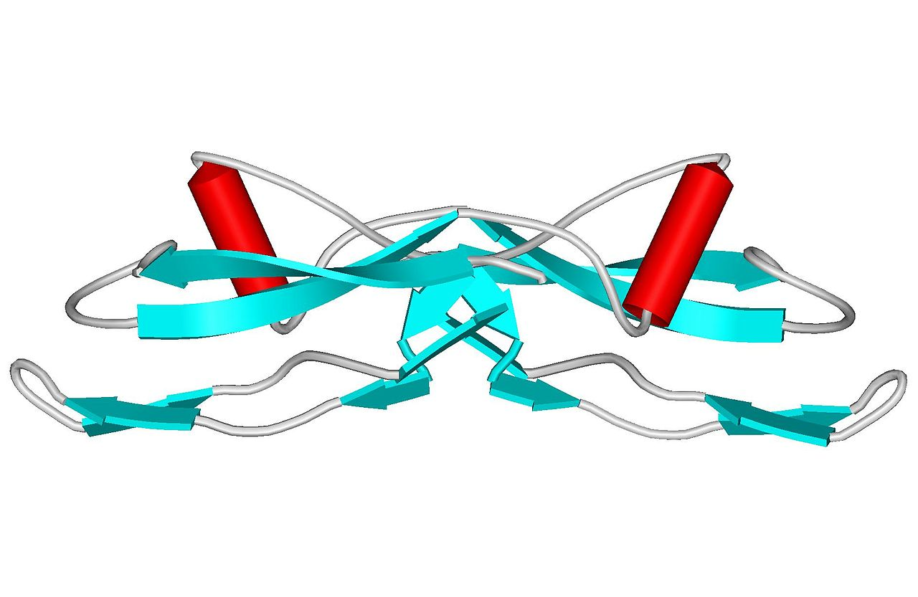

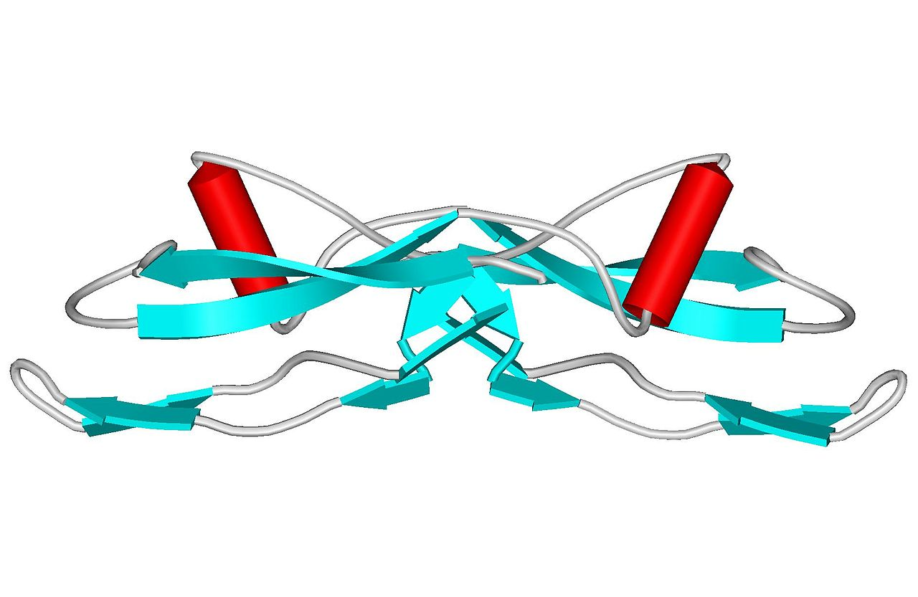

Recently, researchers have discovered another growth factor that may also have promise for PD: cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor, or CDNF. It is quite different than Neurturin and GDNF.

In the brain, these factors are secreted mostly by the neurons and bind to receptors on other neurons. In PD, we are interested specifically in dopamine receptors that tell the neurons to stay alive. There is good genetic evidence that if we cause laboratory animals to lack these factors, the neurons start to die. So, researchers suspect that these growth factors are quite important for the maintenance and health of these cells. GDNF and Neurturin act on other neurons too, but have the most prominent effects on dopaminergic neurons. They also guard new neurons during growth and regulate protein balance (homeostasis). If proteins start to aggregate, collecting abnormally like in PD and AD, these growth factors activate to try to clean out the protein aggregates from the neurons. These wonderful properties have been tested in animal models in the lab since the 1990s.

We are still learning about how these growth factors work, and there are multiple theoretical models describing how they may function in the brain. When these growth factors are made by the neurons in the brain, they are not secreted all the time. Their secretion is controlled by neuronal activity in a strictly regulated manner. Artificially pumping the growth factor into the brain, which is what we do in clinical trials, is not the same as what happens naturally. Figuring out how to mimic the more natural release of these growth factors in the brain may be important in our understanding of how to use these growth factors therapeutically.

How can these growth factors be delivered to the brain?

In any drug trial, figuring out how the drug will get to the brain is crucial. Can it cross the blood-brain barrier? In a normal brain, activity is very important for trophic function. In the PD brain, we don’t know if it functions the same way. Also, where in the brain do we put it?

So far, the approach is usually direct delivery via cannula to somewhere in the brain where there is extensive neuronal change. Gene therapy is a more experimental option for delivery; instead of delivering the growth factor itself, viral DNA is altered safely to turn on the cells that should be producing the growth factor proteins.

Depending on where and how we administer the growth factor, what if the cells there are so sick that the receptors have all faded away and nothing can respond to the growth factor? Or perhaps there may be a state of hibernation rather than a loss of the cell bodies entirely. Either way, there is likely to be the greatest benefit earlier in the disease rather than later in the disease. It may be that future studies would do best to focus on those with early to moderate PD and exclude those with advanced PD, to give the most clinically useful results.

Another important variable: Do you need sustained delivery of the GF, or will sustained delivery cause a pharmacological phenomenon – could the response actually diminish? Perhaps less is more, or maybe it needs to be intermittent delivery via an indwelling cannula and exterior pump. The biology of this isn’t fully understood yet.

Critical elements:

- Location in the brain

- Stage of disease

- Total dose of growth factor

- Delivered continuously or intermittently

It is very challenging to control all of these variables!

The Bristol GDNF trial

In 2018-2019, a UK trial assessed a new delivery method for administering GDNF directly into the brain. It was funded by The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, Parkinson’s UK, and the North Bristol NHS Trust. Forty-one individuals with PD participated in a study to receive GDNF over 9 months in a double-blind clinical trial. All participants underwent surgery to have tubes implanted in their brains to allow infusion of GDNF directly into the affected areas of their brains.

A documentary film followed 5 of the participants of the trial for BBC Two. The resulting film, The Parkinson’s Drug Trial: A Miracle Cure?, does not seem to be available for streaming online, but the trailer is available here.

The Bristol study comprised 3 stages:

- A placebo-controlled pilot study that involved six participants, divided into two groups with only half of the group receiving active treatment via monthly infusion in Bristol.

- A nine-month placebo-controlled clinical trial that involved 36 participants plus the six pilot participants.

- A nine-month open label extension to the trial, where all participants received GDNF.

In early research into GDNF, the results had been quite impressive, showing substantial improvement in motor ability and increased dopamine production visible on imaging scans. For some individuals, the benefits seemed to last for 2 or 3 years after receiving the drug. This was quite exciting. However, some subsequent trials failed to show the same results, participants developed antibodies against the GDNF, and there were concerns about patient safety, so the trials were discontinued.

In hindsight, in some of this research, the issue may have been the device that was used to deliver the GDNF to the brain. This was the impetus for the Bristol study, to evaluate a different method of delivering the drug.

For a detailed but accessibly-written summary of the research on GDNF up to 2019 from Dr. Simon Stott, Deputy Director of Research at The Cure Parkinson’s Trust, visit here.

Ultimately, the Bristol trial did not meet its endpoints, meaning that it did not show significant effects between those who received GDNF and those in the placebo group who did not. It seemed that a substantial “placebo effect” was experienced by those who did not receive the drug.

While disappointing, the trial was useful in a number of ways.

- There were no antibodies detected, which suggests that the delivery method worked better than past methods and did not have any leaks.

- The brain imaging showed an increase in dopamine activity in the participants who received the drug. This suggests the treatment was doing something, even if it hadn’t yet manifested improvement in the physical symptoms.

We can learn a lot from this trial, on many levels. Looking at the neuro-imaging allowed us to explore the biology and validated the theoretical model that GDNF could help regenerate dopamine-producing cells. The 9-month time frame may also have been too short; the first phase of response is going to be the dopamine neurons beginning to come back to life and function again, which takes time. PD is a heterogeneous disease, so variation in different types of PD or different stages of illness might have had an effect as well.

Also, patient-reported outcomes are vital to understand whether the trial is a success or failure, and the panelists felt this was insufficiently weighed in the decision to discontinue the Bristol trial. Lastly, the ability to quantitatively measure PD symptoms in the patient’s home environment would be tremendously valuable, helping us to measure the right things to really understand how the disease – and experimental treatments – are affecting individuals as they go about their daily lives.

Currently, we cannot say that GDNF works. But if we changed the protocol, perhaps someday it might!

Ongoing trials

The AAV2-GDNF for Advanced Parkinson’s trial is currently evaluating the use of gene transfer to deliver GDNF into areas of the brain affected by PD. To read more about this trial, visit here.

Herantis Pharma is developing the other type of growth factor mentioned earlier, CDNF, in a study whose Phase 1-2 were completed earlier this year. The next phase of the trial is ongoing.

You can read the press release here.

To summarize, the panelists made the following main points:

- Growth factor biology is extremely complex.

- We have learned a great deal from the previous studies that have been done on growth factors GDNF, neurturin, and now CDNF.

- They are “cautiously optimistic” that it may be another 5-10 years before we have more definitive results on growth factors in PD.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Question and Answer Session

Q: If I’ve had PD for a long time, am I beyond help?

A: Absolutely not! No one is beyond help, and our goal is to be able to help ALL patients with PD. But when disease is advanced, we suspect growth factors may not be the way forward.

Q: When will we know more about the CDNF trial?

A: Likely not until next year sometime. We learned a lot from the last GDNF trial, and it was the first one that didn’t have any technical problems – that’s clear progress! We also learned several very useful things to improve.