In January 2020, the Parkinson’s Foundation offered a webinar on Optimal Exercise Strategies for Stability, Stamina, and Strength, featuring speaker Joellyn Fox, DPT. She discussed how Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects strength, endurance, and balance; the importance of exercise and how it can impact these aspects of fitness; and tips and tricks to get past some of the hurdles that face people with PD who are trying to increase their physical activity. We at Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach listened to the webinar and are sharing our notes.

To watch this webinar and others from the Parkinson’s Foundation, follow this link to their webinar archive.

The webinar speaker was Joellyn Fox, DPT, lead Physical Therapist at Dan Aaron Parkinson’s Rehabilitation Center, part of Penn Therapy & Fitness in Philadelphia. You can contact the speaker with questions about the presentation at joellyn.fox@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

For additional terrific resources on exercise, see this page on the Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach website.

For a list of local exercise classes in Northern and Central California, see this page on the Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach website.

Now… on to our notes from the webinar.

– Lauren

Optimal Exercise Strategies for Stability, Stamina, and Strength – Webinar notes

Presented by the Parkinson’s Foundation

January 21, 2020

Summary by Lauren Stroshane, Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach

A physical therapist for 14 years, Joellyn Fox has specialized in PD for 11 of those years. She discussed the normal effects of aging versus those of PD, in terms of strength, stamina, and stability, and provided recommendations for how to focus exercises to address those areas specifically.

Changes in strength

In normal aging, muscles reduce over time in size and strength, particularly if they are not exercised frequently. In PD, there are some additional changes: the muscles move more slowly (bradykinesia), which often causes the perception of weakness; there is active resistance when a person tries to move, due to rigidity in the muscles; and there is impaired muscle function.

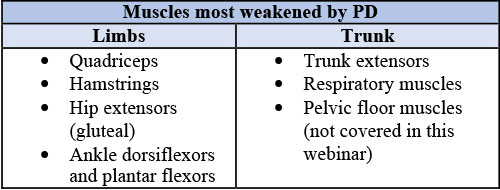

In terms of which parts of the body are most affected by PD, some of the most common areas include the limbs and trunk, as described in the table below.

How to strengthen these muscles despite the effects of aging and PD? Dr. Fox emphasized a technique called progressive resistance training, which involves gradually increasing the amount of resistance the muscles are working against, to slowly build up strength. Progressive resistance training can benefit from the use of workout machines to extend and flex the knees, perform leg presses, or row; alternatively, the use of your own body weight to provide resistance, such as doing squats and lunges, or using elastic bands or a weighted vest can provide a beneficial challenge. Research suggests that a combination of resistance training with other forms of exercise may be the most effective in increasing strength in people with PD.

An isometric contraction is when you hold a particular position, such as holding a squat. A concentric contraction shortens the muscle, such as raising the thigh to a standing position, while an eccentric contraction lengthens the muscle back down to a squatting position. It is good to use a mixture of different contractions during a workout.

Your rep-max is the maximum amount of weight you can move during a particular exercise. For instance, if the most you can lift with your arm is 40 pounds, that is your rep-max.

Dr. Fox recommends working leg muscles at 60 to 80 percent of your rep-max, for two to three sets of 12-20 repetitions of each exercise. In our example, the person would set their weight machine to between 24 and 32 pounds for their workout, then proceed to repeat the exercise 12-20 times as able. They would rest or move on to a different exercise, then come back to the first exercise once or twice more to complete two to three total sets. Strengthening workouts should be done two to three times per week, preferably for a program of 8 to 16 weeks, or indefinitely, if possible.

Changes in stamina

Stamina, or endurance, is the ability to sustain effort over time, whether physical or mental. When stamina decreases, an individual may notice that they can’t keep up with their spouse on a hike, or they get tired faster than they used to while doing chores. Some decline in stamina is common with age, but this is particularly noticeable in PD. Even in early PD, daily activity levels are lower than in healthy controls, but the disparity increases as the disease advances over time. In early stage PD, Dr. Fox noted that individuals tend to have about 200 minutes of physical activity per day (not necessarily exercise, just moving around). As the disease progresses, this daily activity shrinks, down to about 75 minutes in late-stage disease. Her takeaway from this data is to start exercising early – don’t wait until there is already a lot of lost stamina, as it will be more difficult to get it back.

It is possible to regain and build stamina through endurance training, in which you practice sustaining low- to moderate-intensity exercise

Intensity can be assessed subjectively by how challenging the activity feels to you, but it can also be measured with breathing and heart rate. To calculate your maximum heart rate (max HR), subtract your age from 220. Moderate-intensity exercise is typically defined as getting your heart rate (HR) to about 50-70% of your max HR, while vigorous-intensity exercise occurs at 70-85% of your max HR.

For an individual who is 57 years old, their max HR would be 220-57 = 163 beats per minute. When exercising, if their HR was 114, they are likely exercising at moderate intensity. If their HR rises to 138, they are exercising more vigorously now.

The best types of exercise to improve endurance are aerobic activities, meaning they stimulate the heart and lungs to work efficiently and become stronger. Examples include running on a treadmill (which is easier on the joints than running on concrete), cycling (whether stationary or on the street), brisk walking, Nordic walking with poles, and swimming.

Dr. Fox provided two sample regimens for endurance training through cycling. In the first, the individual uses low-resistance cycling with high speed intervals. Use the first and last 5 minutes as warm-up and cool-down sessions at a comfortable cadence. Then do 20 minutes of alternating fast cadence for 15 seconds, then comfortable cadence at 45 to 60 seconds. This represents a total of 30 minutes. She recommends this cycle twice a week for six weeks.

The second cycling regimen Dr. Fox suggested is lower intensity, with an overall speed of 42-70 revolutions per minute, with heart rate not exceeding 50-55% of your max HR. She recommends this cycle twice a week for 40 minutes for 8 weeks total.

As a sample regimen for treadmill endurance training, Dr. Fox explained that the research in this area varies a lot – studies may include a range of different treadmill variables, such as perturbations, robot-assist, split belt, virtual reality, etc. But she recommends those who wish to train on the treadmill run three to five times a week for 30-45 minutes each time.

Nordic walking is another type of endurance training in which you hold walking poles with your arms while striding. You can learn more here: American Nordic Walking. In addition to the benefits of aerobic exercise, Nordic walking lengthens your stride and employs your arms, which can be beneficial for those with PD. However, training in proper use of the poles is needed. Dr. Fox suggested a regimen of three times per week for 10 weeks.

Utimately, whatever form of aerobic exercise you choose, research shows that those who get moderate to vigorous aerobic activity for at least 150 minutes per week have improved function in their daily lives, improved scores on cognitive tests, better quality of life, and slower progression of their PD symptoms.

Changes in stability

Another aspect of fitness that is affected by PD is stability, which can be divided into imbalance and postural instability. Balance describes how your body maintains its position in static, dynamic, and functional states. Postural stability is your capacity to recover and react to situations such as losing your footing or having someone bump into you. Factors that impact your stability include getting older, exercising less, altered gait such as freezing of gait, and cognitive changes. All these factors work together to increase the likelihood of falls.

Among people with PD, 60 percent experience at least one fall, and 39% will experience recurring falls. The majority of these incidents will require medical attention. Those who have slowed walking speed and are not able to stand for very long are most at risk of falls.

Tai Chi is a wonderful form of exercise that helps the body distribute weight evenly and increases leg strength. It can sometimes have an added social benefit, since it is often practiced in a group setting. Dr. Fox suggested doing Tai Chi for one hour, two to three times a week for at least 12 weeks.

A postural instability exercise program developed individually with a physical therapist and done in the community or at home can also decrease the risk of falls. These exercises focus on lower limb strengthening and balance training with both static and dynamic exercises, in individual or group classes typically 60 minutes once a week for 10 weeks.

Movement strategy training and skill-based exercise are other forms of training that can be done with a physical therapist. These focus on attention, rehearsing movements before starting them, visualizing how the movement will go, and learning different cues to help prevent falls. This is usually once a week for 12 weeks.

Stability exercises should be tailored to you specifically; everyone is different. Dr. Fox encourages people to think of exercise as being multifactorial; building skill and strength in one area will help your performance – and quality of life – overall.

Removing barriers to exercise

Question: What is the best exercise for people with PD?

Answer: The one that they will keep doing!

The first step towards exercising is figuring out what motivates you. Is it hope that exercise will slow progression of your disease? Noticing how much better you feel after exercising? Encouragement from family?

Next, think about the times when you wanted to exercise, or planned to, but didn’t. What stopped you? Figure out what the barrier was, and try to remove it. Were your exercise clothes hard to find? Next time, make sure you put them out the night before so they are readily available. Were you unsure what exercise to do or how to start? Next time, make a specific, realistic plan for exactly what you’re going to do.

Guest speaker: Glenn

Glenn previously worked as a physical therapist and has PD himself. He describes himself as an active person most of his life. Now he goes to the gym and uses the spin bike or recumbent bike, treadmill, and weight machines. In addition to the gym, he also does yoga, boxing, meditation, and walking outside. He finds that mixing up the routine is helpful. He also does different things on different days of the week, sometimes alone or with other people. This helps to give some structure and variety to his time.

Despite being active at his baseline, Glenn shared that he has had setbacks too. Last year, he tore his quadriceps muscle while hiking in Vietnam. He had to have major surgery and this altered his exercise routines quite significantly for a while. Setbacks happen, and it’s important to do what you can to work around them and still find ways to be active.

Among the many benefits he notices from exercise, he feels a sense of well-being, and notices his PD symptoms are reduced (tremor, imbalance, fatigue). His restless leg syndrome (RLS) is better, so he has higher quality sleep. And he feels sharper cognitively, like he is more confident.

Question & Answer Session

Q: I am dizzy almost all the time; how can I exercise?

A: Many different things can cause dizziness, so it’s important to first work with your healthcare team to figure out what may be causing your dizziness, then see how you can work around it to exercise safely. Dehydration and low blood pressure are common causes, for instance. Doing exercises while seated or on your back may be an option. Wearing compression garments to support your blood pressure, if that is the reason for your dizziness, can be helpful. Above all, work with a physical therapist to develop a tailor-made program that will permit you to be active in a safe way.

Q: My hand dexterity is quite poor, what can you recommend?

A: See an occupational therapist! They are highly specialized in working with hand issues. They will be able to assess your challenges and recommend strategies and training specific to your issues.

Q: I am an active person and participate in exercise such as skiing, but I still notice issues with not picking up my feet enough when I walk.

A: Work with a physical therapist to focus on amplitude training – this will help you make your movements larger (more normal). You can also try to focus more on walking while you are doing it, and try to avoid distractions.

Q: What do you recommend for freezing of gait (FOG)?

A: It depends on the patient and on how their FOG manifests. Does it improve when you are “on” medication? Is it worse when you are fatigued? Try to involve the whole care team – neurologist, physical therapist, caregiver, etc. – to identify the triggers and causes of your FOG. This will point the way for the physical therapist to identify strategies to combat it.

Q: Does cycling have to be outside or is stationary okay? Also, what do you think about a regular bike that you can mount on a stand in your living room?

A: Stationary cycling can often be better than cycling outdoors – aerobic exercise needs to be sustained to be beneficial, and that can be difficult if you’re riding outdoors and having to stop at traffic lights. There are lots of good stationary bike options. Make sure whatever you choose is stable and won’t tip over.

Some people use foot pedals under their desk, which is good for ankle flexibility and strength, but won’t give you any aerobic exercise.

Q: What do you think of Rock Steady Boxing? How does it relate to physical therapy (PT)? Should I do both?

A: Rock Steady Boxing is a group exercise program that can have many benefits, but is not a substitute for PT. Sometimes the boxing classes are led by a licensed professional, but sometimes it is just someone from the community. Speak with your neurologist or PT to see if they think Rock Steady Boxing could be a good form of exercise for you. Dance for PD can be another option for exercise classes as well.

Q: What do you recommend for someone who has dystonia in their feet?

A: Dystonia is abnormal muscle contraction. If you experience foot dystonia, you’ll need to take it into account when planning exercise, so that you don’t fall or injure yourself. Involve the whole care team and assess how the dystonia presents throughout the day. Does it happen when your medication is wearing off? When you are using certain shoes? Sometimes bracing, relaxation, stretching, or Botox injections can be helpful. Talk with your neurologist and physical therapist to see what they recommend.