Forget stage numbers—focus on what brings you joy and meaning

By Elizabeth Wong, Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach

What if the way we think about Parkinson’s progression is wrong? Traditional staging systems assign numbers to disease severity, but they don’t capture what really matters: your lived experience, your quality of life, and your ability to do the things that bring you joy and meaning.

In early February 2026, Dr. Indu Subramanian, a movement disorder specialist at UCLA Health, presented “Beyond Medications: Living Well with Parkinson’s in the Middle and Later Stages” for the Davis Phinney Foundation. Her message challenges conventional thinking about disease progression and offers a proactive roadmap for navigating what she calls “complex” Parkinson’s—a term she deliberately uses instead of “advanced.”

Why “Complex” Instead of “Advanced”

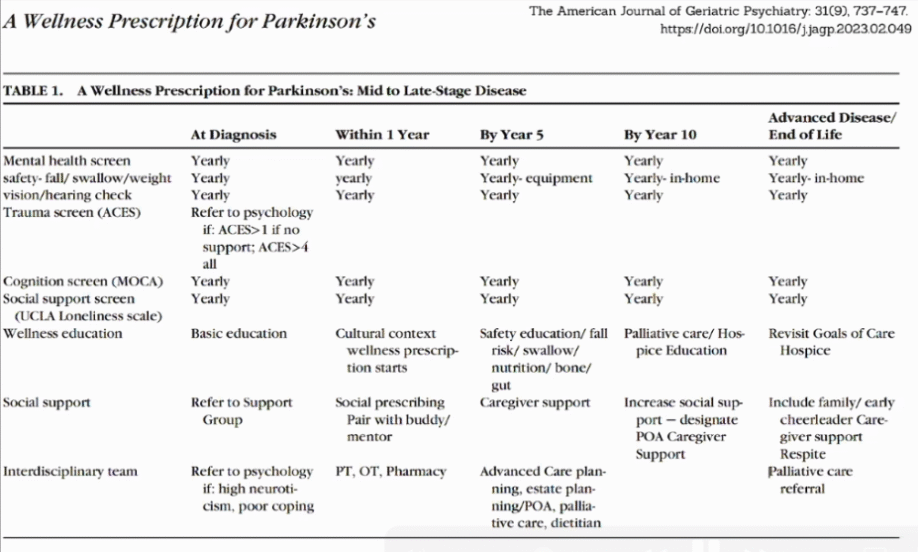

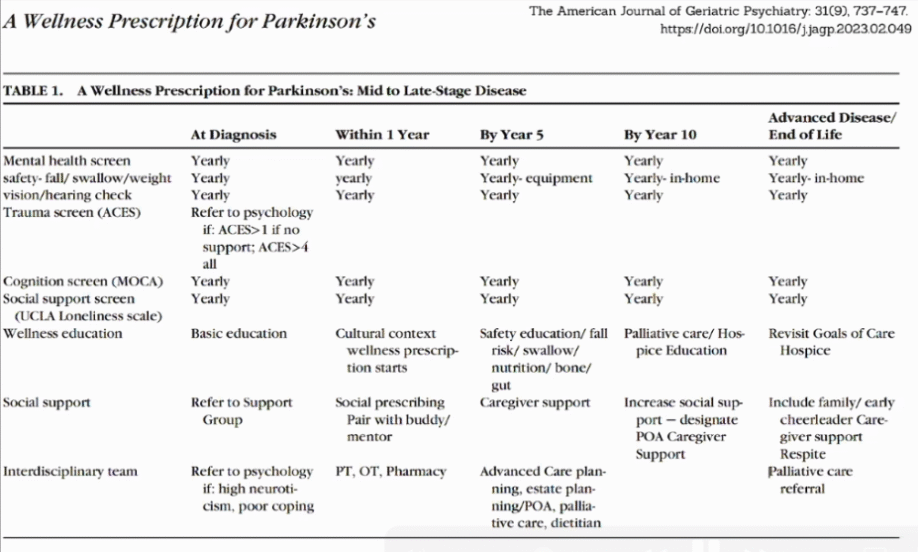

Dr. Subramanian’s presentation was based on a 2023 paper she co-authored titled “The Wellness Prescription for Parkinson’s Mid to Late Stage Disease.” The core message: traditional labels and stages are not helpful. What matters is understanding what brings you joy and meaning, and how to preserve those things throughout the phases of the disease.

Complex Parkinson’s means adapting and working with your care team to maintain quality of life. It means there will be challenges that erupt as problems, but with support and treatment adjustments, you can return to a pretty good functioning baseline. These ups and downs are normal—not inevitable decline.

The key point: There is no point of no return.

Why Traditional Staging Systems Don’t Work

Everyone’s journey with Parkinson’s is different. Some people at diagnosis have minimal motor symptoms but tremendously disabling anxiety that prevents them from leaving home. Others who’ve had the disease for twenty years are hitting their stride, finding new meaning, and have figured out a balance that allows them to live well.

The old staging systems (like Hoehn and Yahr, developed in the 1960s before levodopa existed) focus only on motor symptoms and don’t account for:

- Mental health issues

- Cognitive changes

- Autonomic dysfunction

- The things that actually impact quality of life

What actually matters:

- Symptoms that affect your ability to do things you want to do

- Safety issues (balance, swallowing, fall risk)

- Your functional status and activities of daily living

- Staying active and engaged in your community

Developing tools to be resilient, having support mechanisms, and understanding you’re not alone is key to navigating this uncertainty.

The Wellness Prescription: A Proactive Approach

Rather than reacting to symptoms, the wellness prescription proposes building your care team and support system from day one.

Six Core Pillars

The International Movement Disorder Society wellness prescription (published December 2025, open access) includes:

- Sleep

- Diet

- Exercise

- Mind-body approaches

- Social connection

- Meaning and purpose

This prescription considers cultural context and coping strategies to help people live better every day.

Practical Advice: How to Work with Your Care Team

Write down what bothers you most and how it affects your daily activities. Share this with your care team.

Go to appointments prepared:

- “These are the two things I want to talk about today”

- “The most important thing I want you to understand is [specific concern]”

- “Can you help me with this one symptom?”

- “It’s affecting me because I’m not going to my granddaughter’s house anymore”

Work with your care team to make this the goal for the next 3-6 months.

Focus on what you want to do: Getting to your granddaughter’s house, going to the baseball game, whatever it might be. Focus on the things you really want to do and have your care team help you achieve those things.

The bottom line: Staying active and engaged in your community is key to living well with Parkinson’s, regardless of how complex symptoms become.

Build Your Team Early

Meet specialists before problems become severe:

- Physical therapist before bad falls happen

- Speech therapist before swallowing issues become serious

- Dietitian to discuss nutrition

- Social worker before caregiver burnout or long-term care planning becomes urgent

- Understand treatment options (like DBS) before you need them urgently

Yearly Screening Recommendations for Providers

For mid to late stage Parkinson’s, the wellness prescription includes:

- Cognition: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)—takes 5-10 minutes

- Loneliness/Social Connection: Screening to understand your social networks

- Vision and Hearing: Can change the trajectory of disease, especially cognitively

- Mental Health: Depression, anxiety, apathy screening

- Safety Issues: Swallow function, fall risk assessment

- Bone Health: Bone density screening (especially important for people over 60 with Parkinson’s)

- Social Support: Information about support groups, caregiver support groups, pairing with a buddy or mentor, identifying at least one person to bring to appointments

For Care Partners

Care partners didn’t plan for this diagnosis either. They may go through grief stages (denial, anger, acceptance) and experience uncertainty about their future.

Care partners need wellness too:

- Get sleep

- Exercise

- Maintain social connections

- Get support for what you’re going through

- Recognize burnout and get extra care when needed

Resources for Staying Active and Finding Joy

Exploring different activities can help you discover what brings joy and maintains engagement:

Virtual Art Therapy, Meditation, and Improv Classes for Parkinson’s

https://med.stanford.edu/parkinsons/exercise-therapies/art-meditation-improv.html

Online Parkinson’s Disease Exercise Classes

https://med.stanford.edu/parkinsons/exercise-therapies/live-exercise-classes.html

Dr. Subramanian’s talk was based on a paper in 2023 she co-authored, titled “The Wellness Prescription for Parkinson’s Mid to Late Stage Disease.” Link to a PubMed summary of the article: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37005185/

The webinar recording will be posted to the Davis Phinney Foundation website soon (not posted at time this blog was posted: https://davisphinneyfoundation.org/events/beyond-medications-living-well-with-parkinsons-in-the-middle-and-late-stages/

Keep reading for my detailed notes from the webinar

-Elizabeth

“Beyond Medications: Living Well with Parkinson’s in the Middle and Later Stages”

Speaker: Indu Subramanian, MD, movement disorder specialist, UCLA Health

Webinar Host: Davis Phinney Foundation (davisphinneyfoundation.org/)

Webinar Date: Wednesday, February 4, 2026

Summary by: Elizabeth Wong, Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach

Rethinking Stages: Why Traditional Labels Don’t Help

Traditional staging systems for Parkinson’s disease are not very helpful. Everyone is different with Parkinson’s—everyone’s journey is different. Parkinson’s is a complex disease with many subtypes.

The disease includes motor symptoms (stiffness, slowness, tremor, balance issues) and non-motor symptoms (autonomic nervous system changes affecting blood pressure and gut function, plus a variety of mental health issues). Some of these changes happen even before diagnosis. Classifying or giving people a number on a scale is not a helpful tool. What matters is the lived experience.

Examples of why staging numbers don’t work:

- Some people at diagnosis have very little motor symptoms but have tremendously disabling anxiety and can’t leave their home

- Some people who have had the disease for twenty years are hitting their stride, finding new meaning, having good quality of life, and have figured out a balance and support system that allows them to live well

Parkinson’s changes can happen ten to fifteen years before motor symptoms appear, disrupting sleep, smell, and mood. The concept that there’s a timeline is not the right framework. Instead, focus on understanding what is meaningful and how to preserve the things that bring and meaning throughout the phases of the disease.

What “Advanced” or “Complex” Parkinson’s Means in Research

In the research literature, “advanced Parkinson’s” has been defined by several features:

Motor Fluctuations. When medications that used to work predictably three times a day now need to be taken more often, or when medications don’t work as predictably because of changes in gut absorption. The sense that medications are not as effective or consistent as they once were.

Dyskinesia. As the disease evolves, some people develop dyskinesia (involuntary movements), which presents a new challenge to manage.

Non-Motor Issues. Significant blood pressure fluctuations that make it difficult to go from sitting to standing without feeling dizzy, potentially creating fall risk. This represents a new challenge in managing the disease.

The preference is to think about challenges as they come along and how to cope with those challenges, rather than assigning a stage number.

The Hoehn and Yahr Stages: An Outdated System

The Hoehn and Yahr staging system was developed in the 1960s before levodopa was available as a treatment. These stages were based largely on motor dysfunction:

- Stage 1: Very mild symptoms, maybe unilateral (one-sided) symptoms

- Stage 2: Bilateral symptoms (both sides)

- Stage 3: Balance changes (identified by the “pull test” in clinic)

- Stage 4: Need for help with balance, maybe using a walker

- Stage 5: Bedbound or wheelchair-bound (in the pre-levodopa era)

This staging system is almost sixty years old and was developed before treatments existed. The historical images associated with these stages—largely showing older Caucasian men in various stages of decline, ending up in wheelchairs—represent an inevitability of motor decline that no longer reflects what’s possible with modern treatment.

These old staging systems don’t measure non-motor symptoms, which are hugely important. They don’t account for mental health issues. If somebody has significant cognitive changes or hallucinations, that’s a complex and important safety issue to address, but it might not show up in motor staging.

What Actually Matters: Safety and Quality of Life

Instead of focusing on stage numbers, focus on:

Symptoms That Affect Quality of Life: What symptoms are impacting your ability to do the things you want to do?

Safety Issues: Balance problems, swallowing dysfunction, fall risk—these are challenges that need attention as Parkinson’s advances.

Functional Status and Activities of Daily Living: Are you able to do all the things you want to do? This includes exercising, getting out, meeting people, and staying active in your community. These are things to try to preserve.

When there’s a change in your activities of daily living, bring that to the care team to help guide you.

Why “Advanced” Isn’t the Right Word

Use “complex Parkinson’s” instead of “advanced Parkinson’s.” However, even defining “complex” Parkinson’s became complicated.

None of these staging systems match well with imaging or biomarkers. What’s important is understanding how Parkinson’s is impacting daily life and communicating that with the care team so they can adjust treatment.

There are many treatment options now beyond pills—deep brain stimulation, pumps, and other therapies. The key point: there is no point of no return. There will be challenges that erupt as problems, work with the care team to get support and make changes, and then return to a pretty good functioning baseline. These ups and downs are normal, not inevitable decline.

What Patients Actually Worry About (vs. What Doctors Focus On)

What patients worry about in the trajectory of their disease is very different from what clinicians think is important:

- Identity: How their sense of self changes through the disease journey, from diagnosis through different phases.

- Being a Burden: Interaction with caregivers and wanting to stay independent.

- Cognition: Concerns about thinking and memory.

- Pain: Managing physical discomfort.

- End of Life: Fears about death and dying (a universal concern, but heightened with chronic illness). Questions like: Will I be in pain? Will I have a choice about where I pass away? Who will be around me?

- The Uncertainty: Being given a diagnosis that was not planned for suddenly changes the assumed trajectory of one’s life. Questions arise: Will I see my daughter’s wedding? Will I play with my grandchildren? Will I see my grandson graduate? Will I be able to get pregnant with my next baby (for some younger people)? Will I have access to basic medicine?

Unpredictability and Intolerance of Uncertainty

There’s unpredictability in:

- Symptoms you may experience

- How medications respond over time

- Day-to-day function (Will I be able to attend my 3pm Pilates class, or will my medicine not work and I’ll need a nap?)

- Life changes (How will I go through menopause along with Parkinson’s?)

It’s natural for humans to want certainty and control. When that changes, some people can go with the flow, while others have real intolerance to uncertainty. Providing ways to cope with uncertainty is teachable and changeable. Much of the conversation around advancing disease is about uncertainty—what will I have to deal with next year? What’s the new challenge?

Developing tools to be resilient, having support mechanisms, talking to people, and understanding you’re not alone—that so many people are going through the same experience—is key.

The Road Map: A Proactive Approach

Rather than reacting to symptoms, the wellness prescription proposes a proactive approach.

If you are “at-risk” of PD or if you are diagnosed with PD, screen for social support from day one. Understand who you are—if spirituality is important to you, what makes you tick, what brings you joy and meaning. If you have mental health issues in your past or trauma (like PTSD from military service), this is helpful to know.

Build a team early rather than playing catch up. Talk about the importance of social support—plug in with a buddy or mentor who has Parkinson’s. Check vision and hearing (hearing loss can affect prognosis and should be treated). Discuss proactive lifestyle choices—the wellness prescription for living better every day.

Meet specialists before problems become severe:

- Physical therapist before bad falls happen

- Speech therapist before swallowing issues become serious

- Dietitian to discuss nutrition (though often not covered by insurance)

- Social worker before caregiver burnout happens or long-term care planning becomes urgent

Understand what treatments are available, including surgeries like DBS, before you need them urgently.

Advanced Care Planning

Value the wishes of the person living with Parkinson’s. Sometimes we wait too long to talk about advanced care plans—would you want to go to the ICU? Would you want a feeding tube? These conversations often wait until very late in disease stages when people cannot express their own thoughts, and family members must make decisions for them. Thinking ahead is part of the wellness prescription.

Palliative Care Principles Throughout the Journey

The principles of palliative care should apply from day one:

- Patient-centered care

- Holistic approach

- Valuing spirituality

- Valuing mental health

- Valuing the identity of the person

Providers should prioritize understanding a patient’s unique sources of joy and meaning early in their care to ensure their whole personhood is preserved throughout the entire medical journey.

Impact on Families and Care Partners

Care partners also didn’t plan for this diagnosis. Care partners may go through phases similar to grief stages:

- Denial

- Anger

- Other phases of accepting the diagnosis

They experience uncertainty about their future—retirement might look different, day-to-day life changes around unpredictability.

Care partners can become isolated and stigmatized by association with the person living with Parkinson’s. They may withdraw from their community and lose the support they need.

Care partners need to practice wellness too. Get sleep, exercise, social connection, and support around what they’re going through so they can bring positive energy to their loved one. If burning out, recognize it and get extra care. The same wellness prescription applies to caregivers.

Mortality and Life Expectancy

Mortality is very difficult to talk about and predict. There’s no crystal ball.

PD is affecting more and more younger people. This is a global health care crisis that needs resources and research, although there is no cure, individuals living with Parkinson’s and their families can incorporate what’s important to them, and preserve joy and meaning.

When doctors think someone might pass within a year, there are usually profound signs:

- Multiple ER visits or hospitalizations

- Significant weight loss

- Severe psychosis

- Difficulty absorbing medicines despite best medical management

- Constellation of symptoms

Even then, it’s hard to predict. These conversations about one-year life expectancy are often about getting resources—bringing in palliative care teams for home support and caregiver help.

By and large, Parkinson’s is unpredictable—not like advanced cancer where we have clear studies about time frames.

Psychosocial Adaptation is the process of responding to functional, psychological, and social changes associated with living with chronic illness. This adaptation is influenced by several categories:

- The Illness Itself: Your symptoms and functional limitations. What you bring to the illness (like history of trauma). The disease state and comorbidities.

- Sociodemographic Characteristics: Age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, resources.

- Personality: Coping styles and personality traits. Some people tend to be very positive; others are not.

- Environment: Your support system—family, friends, community. There may also be stigma. Sometimes the community is positive; sometimes it’s not.

- Psychological Reaction: How you’re adjusting to the diagnosis and going through the disease.

There are ways to intervene with some of these things. Socioeconomic status cannot be easily changed, but motor function can be improved with medication,constipation can be treated to address non-motor symptoms, and someone can develop good social support mechanisms. If someone has no social support and is living in isolation, care teams can help change that. If someone lacks coping mechanisms, your care team can plug you into ways to change that.

Understanding how to cope with a diagnosis and live better—allowing someone to feel like they have some control over their outcome—is what the wellness prescription tries to teach.

The Wellness Prescription: Core Components

The International Movement Disorder Society recently published a wellness prescription (December 2025, open access in Movement Disorders Clinical Practice https://movementdisorders.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mdc3.70381) with six core pillars:

- Sleep

- Diet

- Exercise

- Mind-body approaches

- Social connection

- Meaning and purpose

This prescription considers cultural context and coping strategies to help people live better every day.

Wellness Prescription for Mid to Late Stage: Specific Recommendations

The wellness prescription for mid to late stage Parkinson’s includes specific screening and interventions:

- Yearly Screening

- Cognition: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)—takes 5-10 minutes to identify cognitive changes

- Loneliness/Social Connection: UCLA loneliness questions (example: “I often feel isolated” or “I often feel left out”) to understand social networks

- Vision and Hearing: Can change the trajectory of disease, especially cognitively

- Mental Health: Depression, anxiety, apathy screening

- Safety Issues: Swallow function, fall risk

- Bone Health: Bone density screening, especially for women over 60 (also relevant for men over 60 with Parkinson’s), to understand fracture risk

- Education Around Wellness: Why nutrition is important, bone and gut health, proactive lifestyle choices, safety considerations

- Social Support: Information about support groups (if useful), caregiver support groups, pairing with a buddy or mentor, identifying at least one person to bring to every appointment who can take notes and help advocate

Interdisciplinary Team: These providers become important at different phases along the road. Understanding who’s available for referrals:

- Psychologist for coping issues (cognitive behavioral therapy can help with coping)

- Physical therapist

- Occupational therapist

- Speech therapist for swallow

- Dietitian

- Social worker

- Palliative care team

- Yoga and mindfulness practitioners (can help stay present, stay internally focused instead of ruminating)

Question-and-Answer

Question: How common are visual hallucinations, and how can we watch for them?

Answer: Visual hallucinations are pretty common. A Spanish study found that a percentage of people report visual hallucinations even quite early in diagnosis—within the first five years. In Lewy body dementia (a type of Parkinson’s-related condition), hallucinations are more prominent early on. Hallucinations often start subtly: pillows or shadows cast on the wall that look like a cat, or thinking you’re passing somebody in the hall. They can become more significant—actually seeing things. They’re usually visual, not auditory or olfactory in Parkinson’s. This is a safety issue. Visual hallucinations are one of the main reasons people get admitted to a hospital or nursing home. Definitely bring this up with your treatment team.

Question: How common is urinary urgency or incontinence, and how can we prepare for it?

Answer: Urinary urgency (needing to get to the bathroom fast) is experienced by many people. Even with aging, it’s quite common. Urinary incontinence is very disabling and can change whether people want to go out in their community. Once you’ve had one episode, it can make you never want to leave home again. If this happens once, bring it to your provider’s attention. Understand that one episode doesn’t dictate how every time you leave home will go in the future.

Strategies:

- Know where bathrooms are located

- Get to places early so you can use the bathroom and get the lay of the land

- Some people wear pads or certain types of protective underwear as a precaution

- Specialists called urologists or urogynecologists can help

- Bring this to your provider to get support

Don’t let one incident of urgency or incontinence lead to catastrophizing—thinking every day from now on will be defined by that. Put it in context. Hope for the best but plan for the worst. Make decisions to help yourself, but stay active and engaged in your community.