In late March, the organization Help for Alzheimer’s Families offered a webinar on caring for someone with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Our summary of this webinar focuses on the movement disorder variants of FTD: corticobasal syndrome (CBS) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). The speakers included Matthew Sharp and Deena Chisholm from the Association of Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD). They discussed how FTD differs from other types of dementia; signs and symptoms of FTD; and what resources are available for families. We at Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach viewed the webinar and are sharing our notes.

The speakers on the panel included:

- Matthew Sharp: program manager for the Association of Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD)

- Deena Chisholm: education program manager for the AFTD

This webinar was recorded and can be viewed here.

If you have questions about the webinar, you can contact Help for Alzheimer’s Families via their online form.

Or contact the Association of Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD):

- HelpLine: 866-507-7222

- Email: info@theaftd.org

The AFTD website offers many useful resources for those with FTD and their families.

In March, we summarized a related webinar covering the basics of FTD, focusing on CBS and PSP, the movement disorder variants of FTD:

“Frontotemporal Degeneration: A complex disease”

Now… on to our notes from the webinar.

– Lauren

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Caring for someone with frontotemporal dementia – Webinar notes

Presented by Help for Alzheimer’s Families

March 19, 2020

Summary by Lauren Stroshane, Stanford Parkinson’s Community Outreach

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the most common cause of dementia in people under the age of sixty, but is often misunderstood and misdiagnosed. The speakers started with an overview of FTD and how it differs from other types of dementias.

How does FTD differ from other types of dementia?

“Dementia” is an umbrella term for changes in behavior and cognition that affect how a person functions in their daily life. There are lots of different causes, some of them reversible with treatment. When it comes to neurodegenerative disorders, these diseases worsen over time and, as yet, have no cure. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common and widely known of these. Dementia caused by neurodegeneration is, unfortunately, not curable.

FTD itself is another umbrella term, covering multiple overlapping neurodegenerative disorders. This summary will mainly focus on the movement disorder variants of FTD: corticobasal syndrome (CBS), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP).

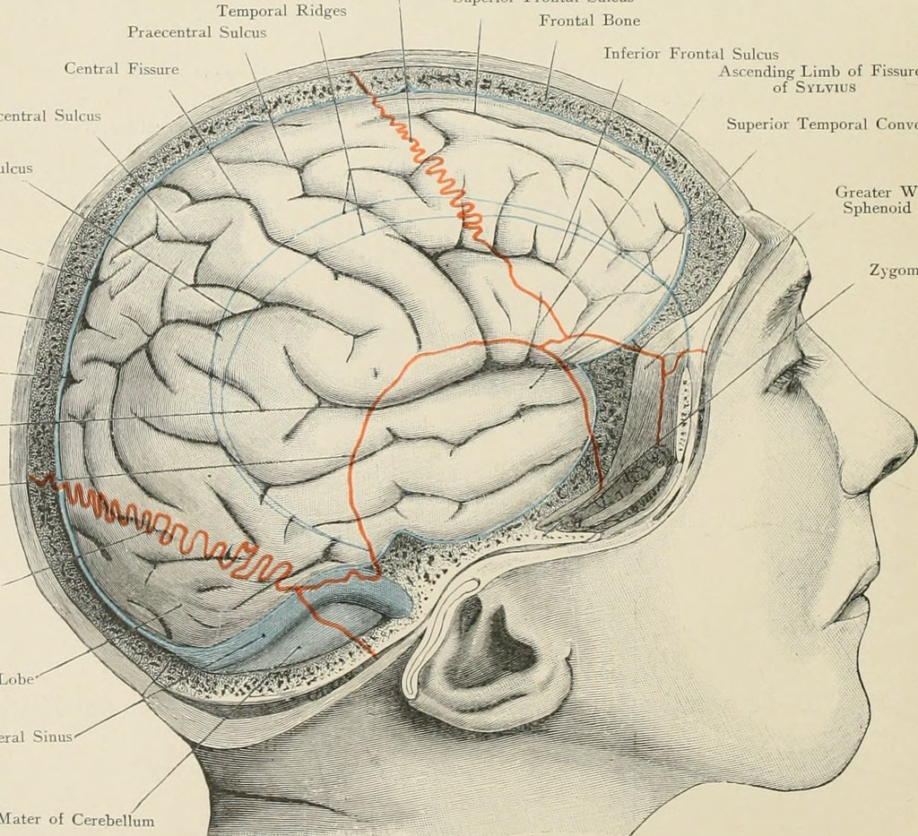

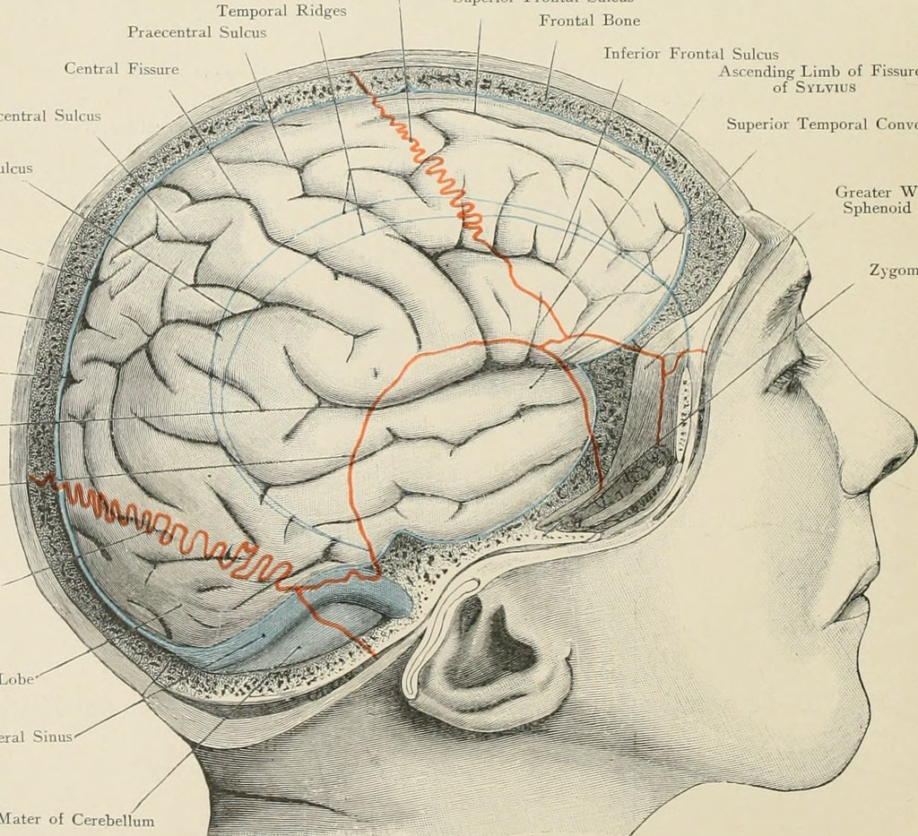

The regions of the brain that are mainly impacted by FTD are the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobes affect our executive function: the ability to make decisions, pay attention, make and execute plans, think, and multitask. Judgment, personality, impulse control, and motor function are also regulated here. The temporal lobes are mainly involved in memory, language, and speech.

People with FTD typically develop symptoms in their 50s, but they can occur much earlier – even as early as one’s 20s – or much later, even into the 80s. The earlier age of diagnosis in FTD is one of the ways it is often distinguished from AD, which becomes more likely with age. The major symptom of AD is memory, whereas FTD generally does not substantially alter memory early in the disease. Another difference is their prevalence – AD is far more common than FTD, which is comparatively rare.

It is partly due to FTD’s earlier onset in life that the disease can be so devastating: it often develops while the individual is in the prime of their life, with many responsibilities such as work and family.

Signs, symptoms, and behaviors of FTD

Cognitive changes that can occur mainly reflect changes in executive function: activities that require attention, such as reading books or watching movies; making and executing plans; and the ability to reason and think adaptably. Changes in behavior can also occur, and may include apathy, lack of inhibition, impaired judgment, and loss of empathy. Anosognosia, the inability to have insight into one’s own behavior or symptoms, can also occur.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a variant of FTD that is characterized by imbalance and unexplained falls; stiff, slow movements; and trouble coordinating eye movements. To learn more about PSP, read more here.

Corticobasal syndrome (CBS) is an FTD variant that causes rigid, slow, reduced movements, apraxia (inability to perform tasks or movements despite knowing how), and limb or fine motor control. To learn more about CBS, read more here.

On average, the diagnostic journey takes 3.5 years. There are no biomarkers or imaging that can definitively diagnose FTD; it is a clinical diagnosis, meaning it is based on the history and symptoms when the individual comes to clinic. The only truly definitive diagnosis is through a brain autopsy, after death, to determine the pathology that was present. The input and observations of the family are essential, since the affected individual may be a poor historian or may not have insight into their own symptoms or behavior changes.

Those with CBS or PSP are usually diagnosed by a neurologist or movement disorders specialist; their movement changes tend to be the most prominent symptoms of illness rather than behavior.

What resources are available for families?

It can be difficult to find help specific to FTD, given how comparatively rare and poorly understood it is. Some healthcare providers may not have ever heard of it before.

The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (AFTD), which employs both webinar speakers, is a wonderful resource for families. Their website contains large amounts of helpful information, ranging from web pages for those who are newly diagnosed, to legal and financial planning, to information on clinical trials. They have an archive of past webinars and lists of community groups that meet virtually right now.

They also offer a toll-free helpline and can also respond via email. The helpline goes to an answering machine and their volunteers will respond as soon as possible, usually within 2 days.

- HelpLine: 866-507-7222

- Email: info@theaftd.org

Commonly asked questions include requests for help looking for community services.

The Comstock Grant Program allows AFTD to offer financial assistance directly to some in the FTD community, recognizing the severe economic toll this disease can take on families. These include annual grants for respite care, travel, and quality of life expenses. Learn more here.

Deena Chisholm writes a free, quarterly newsletter called Partners in FTD Care. Each installment highlights different aspects of care or challenges and offers suggestions and resources for coping. To sign up, visit here.

How can I or my loved one participate in clinical trials?

The speakers recommend signing up for the AFTD registry, a secure database that collects information from people diagnosed with any of the FTD disorders, as well as from their loved ones, with the goal of furthering our understanding of these diseases and facilitating research efforts. Right now, the registry is mostly useful for natural history studies to understand the course of the illness. In the future, they hope there will eventually be clinical trials and studies of potential biomarkers; the registry can function as a vital communication tool to alert its members of new trials.

The federal database of research studies, is another good source of information on available trials for a vast array of different conditions. One can search by diagnosis or location.